Misinformation about a viral disease that infects cattle is spreading on social media in India.

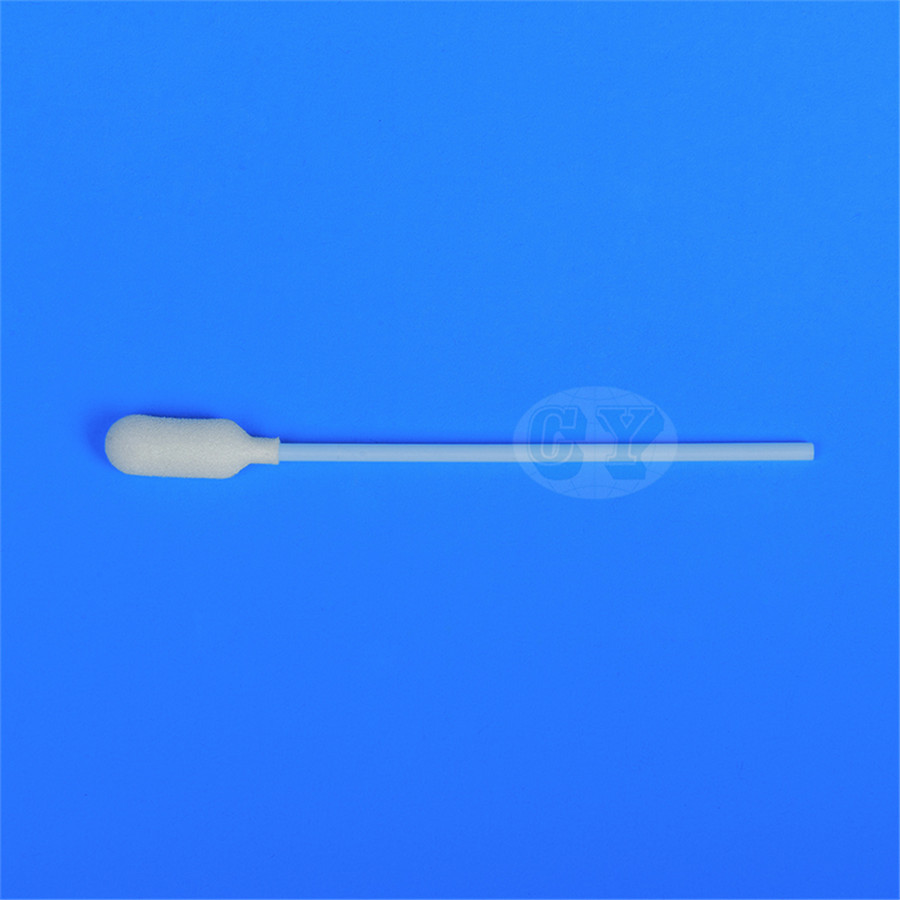

Lumpy skin disease has already infected over 2.4 million animals and has led to over 110,000 cattle deaths in India, according to latest data from the government. Transport Culture Medium

India is the world's largest milk producer and has the world's largest cattle population, but the infection is threatening livelihoods of farmers in the country. Meanwhile, misinformation has made some people wary of consuming milk. We debunk three false claims about the disease.

Many viral social media posts falsely claim that milk has become unsafe for human consumption due to the spread of lumpy skin disease, and that drinking milk from an infected animal will lead to the development of a skin disease in humans as well. The posts are often accompanied by images of visibly diseased human bodies covered in lesions, meant to create fear.

"I have seen many such claims in social media groups of the dairy industry. Those who circulate such claims are not responsible - they share it as though it is information that only they possess," Poras Mehla, general secretary of an association of 6,000 dairy farmers in the northern Indian state of Haryana, told the BBC.

Dairy farmers are suffering due to the false claim. "I noticed this claim on social media and even heard that some people who believe it are throwing away milk," says Manav Vyas, a dairy farmer and the manager of a cattle shelter in the western Indian state of Rajasthan. "Dairy farmers who are already under economic stress after losing cattle to lumpy skin disease are now facing the added burden of stigma from people who refuse to buy milk."

Searches for "can we drink milk of lumpy skin disease cow" grew by more than 5,000% in the past 30 days according to data from Google Trends.

In reality, lumpy skin disease is not a zoonotic disease - which means it is not naturally transmissible from animals to humans. In a 2017 report, the UN's Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) confirmed that lumpy skin disease does not affect humans.

This has also been confirmed by the Indian government's Indian Veterinary Research Institute (IVRI). "Till date there is no evidence of any animal to human transmission," Dr KP Singh, Joint Director of the IVRI told the BBC. "However, a suckling calf can get the infection from the milk of an infected cow."

As for the images of human bodies covered in lesions that usually accompany the false posts, the disease can be accurately identified by collecting samples and sending them to a diagnostic laboratory, according to Dr Singh. "We cannot pinpoint the disease on the basis of symptoms or lesions, as there are many diseases which have similar symptoms."

Misinformation about the origin of the lumpy skin disease is also doing the rounds on social media. This includes the false claim that lumpy skin disease has entered India from Pakistan, and that it is part of a Pakistani conspiracy against India's cows. Cows are considered sacred by India's majority Hindu population.

In reality, lumpy skin disease first originated in Zambia in 1929. For a while it remained endemic to sub-Saharan Africa, but it has since spread to countries in North Africa, the Middle East, Europe, and Asia.

In Asia, the disease was first observed in July 2019 in Bangladesh, China and India, according to a report by the FAO. At the time this FAO report was published in 2020, the disease had not yet been detected in Pakistan - so it can be concluded that the disease was detected in India before it was detected in Pakistan, and that the claim that the disease spread from Pakistan to India is false.

This was further confirmed by Dr KP Singh, Joint Director of the IVRI. "The disease entered India from Bangladesh - not from Pakistan - due to natural animal movement and transport at the border. Cases in Bangladesh were reported earlier than cases in India. In Pakistan, cases were reported later, after being reported in India," he told the BBC.

Misinformation about lumpy skin disease has been compounded with anti-vaccine conspiracies on social media.

A video of cattle carcasses in a dumping ground is viral on social media platforms, with the claim that tens of thousands of cattle "suddenly started to die after being given a vaccine by the Indian government." These claims have thousands of retweets and have been viewed over a hundred thousand times.

While the video is genuine, the accompanying claim - that cattle are dying after being administered the vaccine - is false. Large-scale vaccinations are the most effective way of limiting the spread of the lumpy skin disease, according to the FAO.

A cattle vaccination programme is currently underway in several states across India, and the goat pox vaccine is currently being used as it provides cross protection against lumpy skin disease. Indian researchers have also developed a vaccine against lumpy skin disease, which they have been working on since the virus was first detected in India in 2019. This vaccine is yet to become commercially available.

Millions of animals have already been vaccinated and recovered across India. "The only solution currently available is the goat pox vaccine. It is a very good vaccine and gives 70-80% protection against lumpy skin disease without any side effects. We are observing this impact in the field and getting good feedback," Dr KP Singh told the BBC.

Rishi Sunak to become next UK prime minister

Russia reinforcing occupied southern city - Ukraine

Xi Jinping's party is just getting started

Hollywood reflects as new Weinstein trial begins

The top US Senate races to watch in 2022 midterms

New ground as tech aims to help boost soil health

India's virtual stars whose real faces you won't see

What these buzzwords say about Xi's China

India celebrates Diwali with dazzling lights

New East African oil pipeline sparks climate row

'When I couldn't fix George, I climbed a mountain' Video 'When I couldn't fix George, I climbed a mountain'

The cost of occupation in Kherson region

The most disgusting films ever made

How job insecurity affects your health

The word Tolkien coined for hope

Antibody Test © 2022 BBC. The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Read about our approach to external linking.